Originally published on TASTE BUD.

Written by Mennlay Golokeh Aggrey

Reading Time: About 6 minutes.

With a staggering $802 million made from the pumpkinspicification of a nation, many of us are blissfully unaware of the disturbing legacies behind its key spice components. The Pumpkin Spice phenomenon that’s been haunting us every fall for the past 20 years has now, I’m disheartened to report, made its way to Mexico. Don’t get me wrong, I can vibe with a cozy mix of nutmeg, cinnamon, clove, ginger, and hints of Native American heirloom squash or gourd cultivars Indigenous to South America and West Africa. But the commodification and violent past of this autumnal flavor profile is just as nauseating culturally as its intense artificial flavors.

The sinister history of a spice collection

Last year, Washington Post reporter Maham Javaid published a controversial article shedding light on the violent past of Pumpkin Spice(s). Here’s how it went down: the Dutch East India Company's violent conquest of the Indonesian Banda Islands in 1621, where thousands of bodies indigenous to the islands were slaughtered, enslaved, or starved to death is a textbook case of genocide. The population went from 15,000 to a few hundred—wiping out a people—just for nutmeg. The Dutch and many in the spice war came for nutmeg due to the legend that it could cure plagues, sharpen the mind, and increase libido. It’s wild to think that the war of spices started in part due to European colonizers’ desire to season their rotten meats and cure diseases contracted from obscenely poor hygiene… In the article, historian Adam Clulow chillingly referred to this occurrence as “the first instance of corporate genocide,” which highlights how colonial ambition transformed a flavor into a weapon of oppression.

“the first instance of corporate genocide,” which highlights how colonial ambition transformed a flavor into a weapon of oppression.

As the Dutch used horrifying measures to monopolize nutmeg, they quickly moved on to the nearby Ambon Island for another spice called ‘cengkih’, ‘lalpari’, or clove. This time their rule over this spice was obtained by a mix of genocide and a bloody battle between the Netherlands and England.

Clove’s focal point of war

As clove became the central focal point of another war that the Portuguese initially won, the grab for domination of spices was drawn out, complicated, and terrorizing. Power would soon transfer from the hands of the Dutch to the English. In the past, they would work with Indigenous traders to peacefully exchange their coveted spices. However, the English, Dutch, and many other nations decided to eliminate the middleman to establish their own spice empire. The history of clove is similar to that of nutmeg in that the Dutch East India Company also sought to monopolize the clove trade by employing its same brutal tactics. This culminated in the 1623 Massacre of Ambon, where the Dutch again slaughtered many locals who courageously resisted their oppressive rule.

1753 Map of Ambon and the Banda Islands with note in French, ‘C’est dans ces Isles que croit la Muscade or “It is on these Isles that Nutmeg grows”

The violent spread of cinnamon

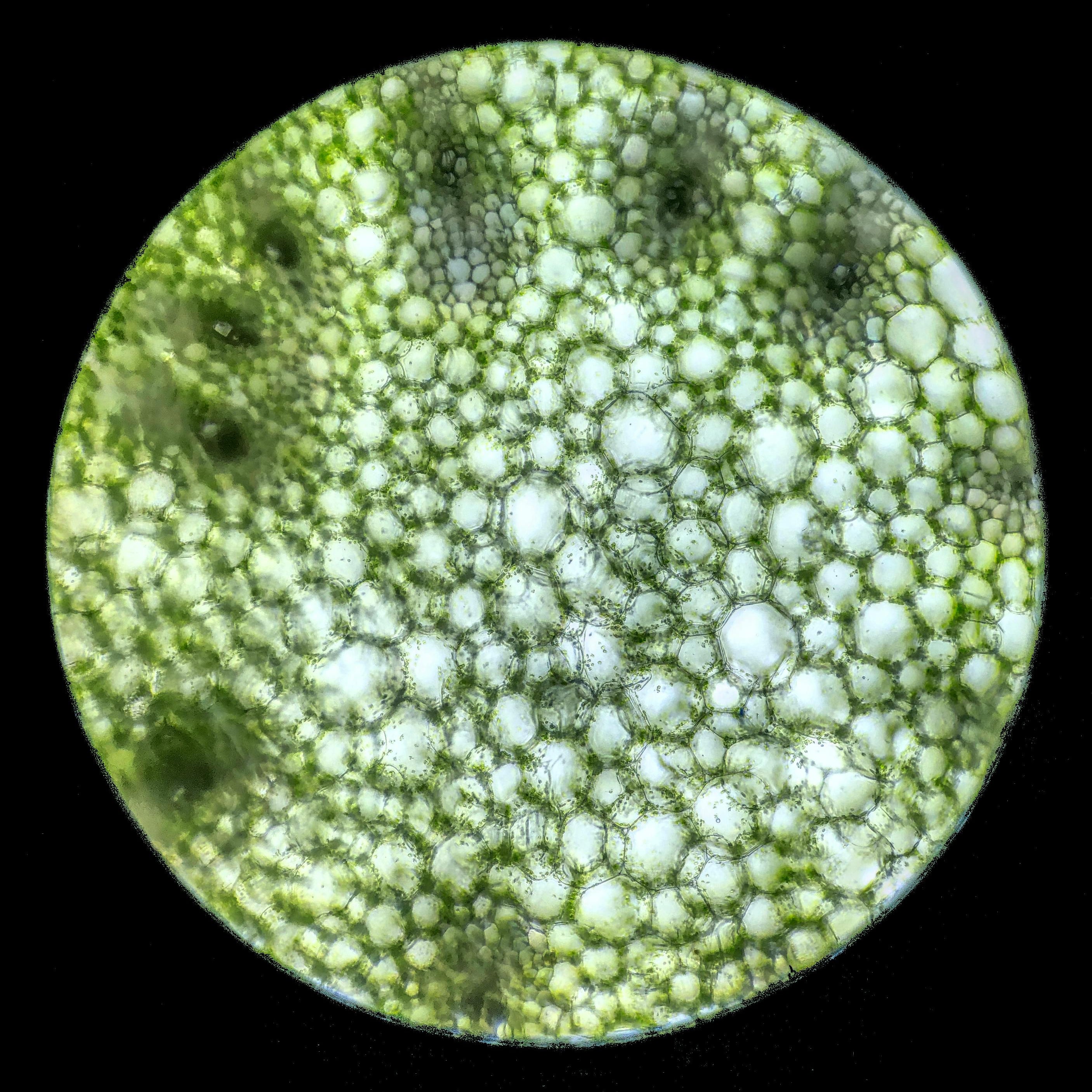

Native to Sri Lanka, and now widely and invasively grown in parts of Africa, cinnamon was well-known in ancient Egypt as an ingredient to preserve food and provide additional mystical powers. Check TikTok, if you want to see how far modern civilization has taken it. It initially was civilly purchased, traded, and migrated back and forth between Asia, the Middle East, and Africa by Arab traders. Cinnamon was notably first referenced in ancient Chinese herbal taxonomy books of 3000 BC and was prescribed as a beneficial plant bark ally for digestive problems—similar to Emperor Shen Nung’s (the father of Chinese medicine) pharmacopeia text that first mentioned cannabis in around 2800 BC.

Cinnamon was unfortunately not all peaceful Arab trading, and eventually became violent as European powers scrambled for its control. The Portuguese, established market control on cinnamon, not only taxing it heavily but also enforcing inhumane labor practices in the regions where it was cultivated. This exploitation prompted fierce competition, igniting conflicts such as the Cinnamon War between the Dutch and the Portuguese. Ultimately, the Dutch seized control and continued its cycle of violence and human cost at the hands of imperial ambition.

Ginger’s route of terror

Ginger root became another war-worthy spice during the so-called Age of Exploration aka exploitation. In the 15th century, the Portuguese established control over its key spice routes from southeast Asia, through the Middle East and the Caribbean. It laid the groundwork for the brutal competition that followed similarly with the other “pumpkin spices”. So if you’re still with me, by the 17th century, the British had taken the lead, with the East India Company after the Dutch—now dominating trade from India and the Caribbean. The British put their brand on spice violence by the mid-18th century which was marked by profound exploitation and oppression.

Plantations in the Caribbean soon followed, particularly during the 17th and 18th centuries making ginger a valuable cash crop in part due to the region's perfect climate conducive to its cultivation and the agrarian talents of the enslaved peoples. Later, the British, Spanish, and French all established plantations to grow ginger alongside sugar and tobacco. People were kidnapped from Southeast Asia, Africa and the Caribbean islands and forced to perform labor.

“Whenever foods enter the pop culture lexicon... it’s important to recognize how it reached us.” — Sarah Wassberg Johnson

Nutmeg, clove, cinnamon, and ginger—each with a history marked by exploitation is not merely spices combined in cute drinks and premade baking mix, they are silent symbols of the deplorable past. Food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson emphasizes the importance of acknowledging that, “Whenever foods enter the pop culture lexicon... it’s important to recognize how it reached us.” The nostalgia some of us have for pumpkin spice lattes should force us to question the centuries of violence and exploitation that enabled their mass production and devastation to communities and lands.

Okay, Mennlay, why is carrot grapefruit juice a better alternative?

In full transparency, my hater energy towards pumpkin spice and my love for carrots and grapefruit juice have a lot to do with the insane wealth made off of centuries of Indigenous people’s pain. BUT it’s also connected to my research on orange beta carotene-rich foods in response to being a 41-year-old teenager with naturally deteriorating eyesight.

Carrots and grapefruit are also a chefs’s kiss. The sweetness of the carrot cuts through the bitterness of the toronja, and the bitterness of the grapefruit cuts through the thickness of carrot juice. It’s one of my favorite new eye-supportive anti-pumpkin spice drinks for fall.

The Recipe —

yield: 2-4 servings (apx 16 ounces of juice)

time: 10 minutes

What you need:

- 10 carrots, peeled or not

- 5 grapefruits, peeled

- *optional* 1/2 cup filtered water, depending on desired concentration

- *optional* 2-inch piece of ginger root, peeled

- *optional* 5 fresh cannabis leaves

What do do:

Using Blender:

- Peel and rough chop all ingredients into about 2-4 inch-sized pieces.

- Add 1/2 cup of cold filtered water and blend until silky smooth and liquidy. Slowly add in more water if necessary.

- Using a metal strainer, milk bag, cheesecloth, or clean tea towel, strain juice until it renders all the juice you can squeeze out.

(if making low-waste carrot soup, separate grapefruit and blend into two steps, reserving the carrots and ginger pulp separately.)

Using Juicer:

- Peel and rough chop all ingredients into about long 2-4 inch long pieces.

- Process through juicer and enjoy!

(if making low-waste carrot soup, separate grapefruit and blend into two steps, reserving the carrots and ginger separately.)

Carrot Potato Ginger Soup Recipe—

What you need:

- Discarded carrot and ginger pulp

- 2-3 potatoes or sweet potatoes washed and roughly chopped

- 2 tablespoons of onion, garlic, shallots, or all three

- 1 bay leaf

- Salt, pepper, cayenne and turmeric to taste

- 2 cups of water of vegetable broth

- 2 tbsp olive or sesame oil

What do do:

- Peel or leave on the skin and boil potatoes until tender. Strain.

- In the same pot, drizzle olive or sesame oil. Add about two tablespoons or more of aromatics, whatever you have on hand, (onions, garlic, shallots) and sauté on medium heat until fragrant, about 1-2 minutes.

- Remove carrot pulp (and ginger if using) from the juicer strain cloth or juicer machine and add to the pot with salt and pepper to taste, a sprinkle of cayenne, turmeric, and 1 bay leaf.

- Add 2 cups of water or vegetable broth on high heat and bring to a simmer for about 20-30 minutes until the liquid has reduced and the soup has turned slightly less vibrant but smells divine.

- Using an immersion blender, regular ass blender, or wooden spoon, blend into a the soup is at whatever consistency preferred.

- Serve with a side of rice; top with cream, roasted sunflower seeds, pepitos or enjoy plain as is!