Much talk about cannabis and its effects on the body have to do with acute intoxication and how the molecules in cannabis, like THC and CBD, affect the brain. But like any medicine or chemical substance, however natural, cannabis also affects other body systems, too, like the gastrointestinal system.

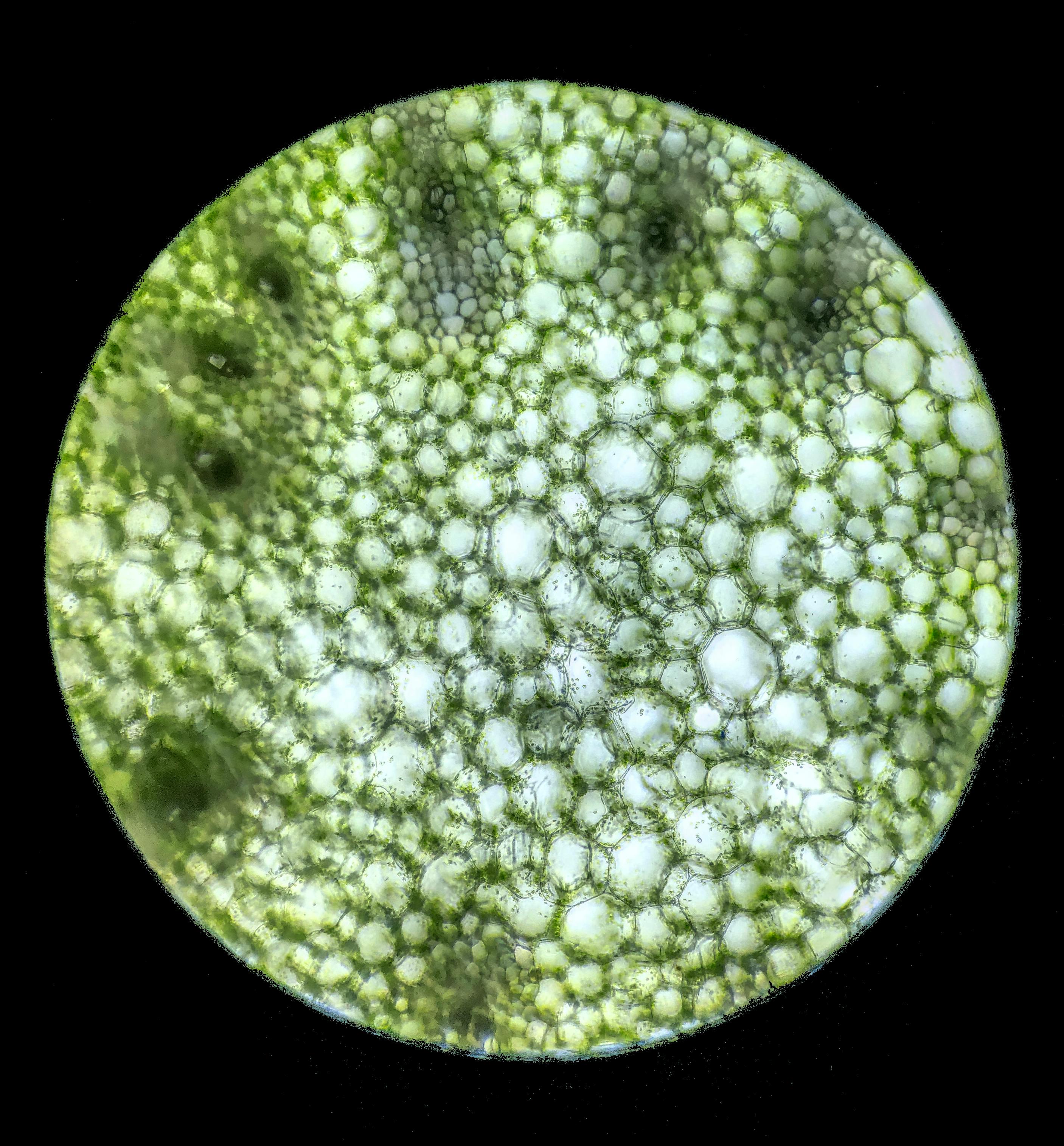

Cannabis and digestion are closely linked for a simple reason: the stomach and intestines are rich with cannabinoid receptors. That circuitry, part of the endocannabinoid system, helps regulate motility, secretion, immune tone, and visceral pain. When THC activates CB1 receptors in the gut and CBD nudges related pathways, it can change how nausea, appetite, and cramping feel in real time.

The strongest clinical foothold remains nausea. THC’s antiemetic effect is well established in oncology, including as dronabinol for patients who cannot keep food or fluids down during chemotherapy. Appetite often follows. Those results are why people living with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have explored cannabis on their own. The intuition makes sense: the endocannabinoid system sits inside the same reflex loops that drive urgency, spasm, and pain.

What the data show is more modest than the anecdotes. Small randomized trials and observational studies in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis report better abdominal pain scores, improved appetite and sleep, and higher quality-of-life measures for some patients. Objective signs of disease control, like endoscopic healing or inflammatory markers, are inconsistent. Symptom relief, yes. Reliable control of inflammation, not proven. In IBS, early trials and patient surveys suggest reductions in cramping and bowel urgency for some subtypes. Dosing, ratios, and ideal candidates are not settled, and effects may cut both ways: slowing motility can help diarrhea-predominant IBS while worsening constipation for others.

How cannabis is used matters as much as what is used. Inhalation acts within minutes and fades in a few hours. That speed can help during sudden waves of nausea or spasm and bypasses the first pass through the liver when eating is hard. Oral products arrive slowly and last longer. After swallowing THC, the liver converts part of it into 11-hydroxy-THC, which many experience as stronger and longer lasting. That can be useful for sustained coverage once eating and drinking are possible again, but it also explains why accidental overconsumption happens with edibles. Many patients land on a hybrid: a small inhaled dose for fast relief, paired with a carefully measured edible for a longer tail.

CBD is not a stand-in for THC. It can modulate nausea and gut sensation through serotonin and TRPV1 signaling, and it often tempers THC’s psychoactivity. It does not reliably stimulate appetite and, at high doses, can cause diarrhea in some users. Product format also matters for comfort: smoking works but irritates airways; vaporizing flower at reasonable temperatures is gentler; oral formats avoid the lungs but may aggravate reflux if they are chocolate, mint, or citrus based.

There are limits that patients and clinicians should recognize. Cannabis is not a stand-alone therapy for IBD. Biologics and other disease-modifying drugs remain the backbone for preventing strictures, fistulas, and hospitalizations. The most pragmatic clinical approach treats cannabis as an adjunct for discrete symptoms: nausea, poor appetite, nocturnal cramping, or visceral pain. The safest way to test it is slow and documented. Keep a simple log of product, dose, route, timing, and symptoms. Change one variable at a time and give it room to show whether it helps or hurts. Share that record with a gastroenterologist, particularly if other medications are in play.

There is also a GI condition linked to heavy, long-term cannabis use that deserves clear naming. Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) shows up as cycles of severe nausea, vomiting, and belly pain in frequent users, often daily. A distinctive clue is temporary relief with very hot showers or baths. The mechanism is still being worked out and likely involves chronic overstimulation and rebound in the same pathways that usually suppress nausea. During an acute episode, people often need IV fluids and supportive medications; topical capsaicin can help some. The only reliable long-term fix is stopping cannabis. CHS should not dominate the conversation, but consumers, budtenders, and clinicians should know the red flags and act early.

Other practical details matter. Potency chases can backfire in GI care; more THC is not always more relief. Terpene and minor-cannabinoid claims are ahead of evidence. “Indica vs. sativa” is branding, not physiology. Timing can be as important as dose. If mornings are unpredictable, a very low oral dose at night sometimes steadies the next day more than anything taken at breakfast. People with reflux often learn that the edible’s base—not its cannabinoids—is the trigger.

Research is trying to make the tools sharper. Formulators are testing capsules that release cannabinoids later in the intestines, aiming for local action with fewer systemic side effects. The microbiome is in the frame; the endocannabinoid system and gut bacteria appear to influence each other, though practical takeaways are not ready. Better trials that separate IBS subtypes, measure hard outcomes in IBD, and study the actual product profiles people buy would help move guidance from “try carefully” to something closer to protocol.

The bottom line, stripped of hype and panic, is practical. Cannabis can be useful for certain GI symptoms, especially nausea, appetite loss, cramping, and visceral pain. It is not a cure for IBS, and it does not replace disease-modifying therapy in IBD. Use routes and doses that match the problem at hand; write down what happens; involve a clinician; stop and seek care if vomiting cycles or hot-shower relief appear. The gut has the wiring to respond to this plant. Respect that, and it is easier to find the narrow window where it helps more than it harms.